The Writer's Practice: Erika Swyler

Image: BJ Enright

Sit down for four hours every day. Drink coffee.

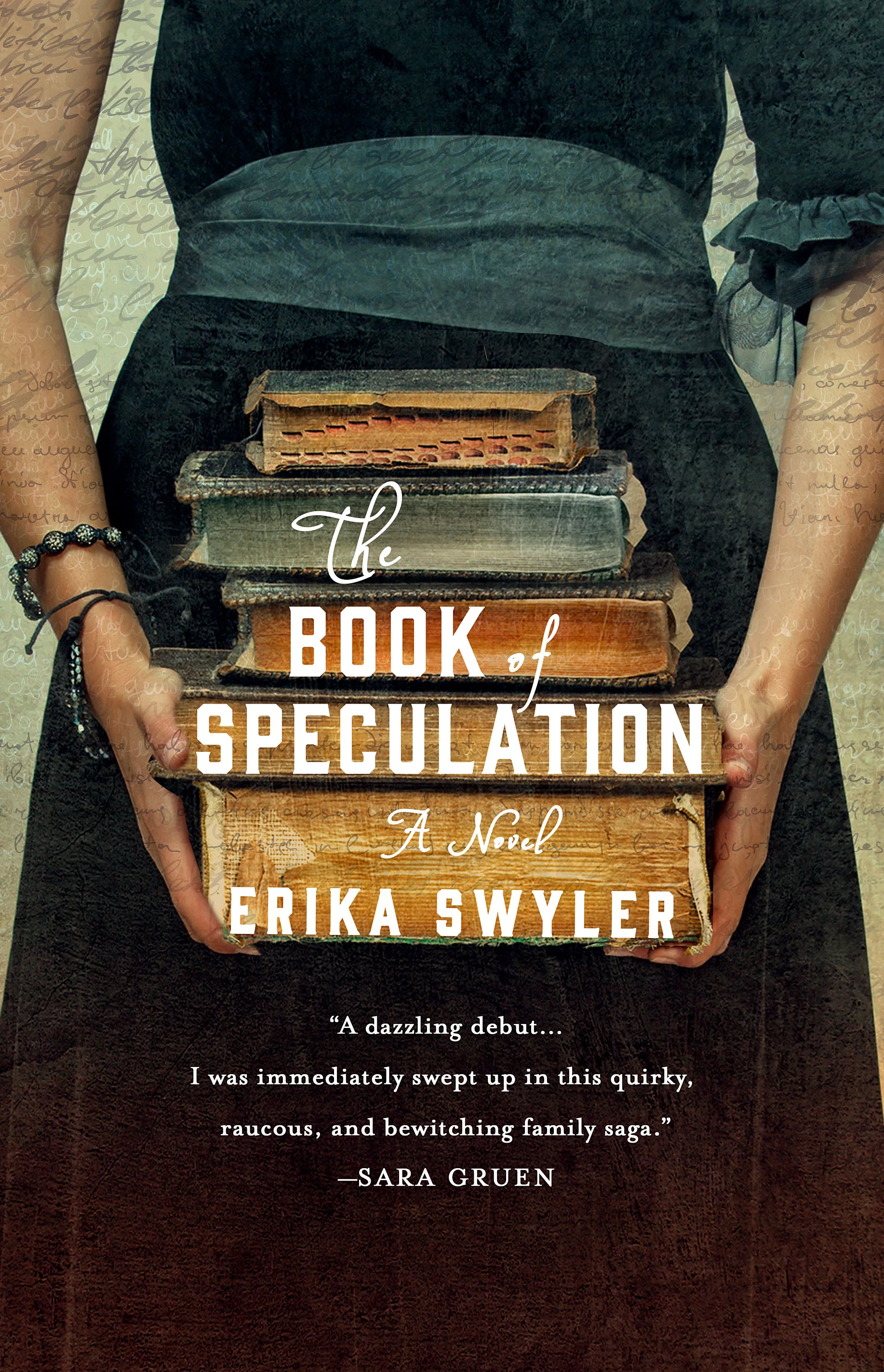

Erika Swyler's writing practice is summed up in two basic phrases, practical sentences nothing like the lovely prose she spun in her first novel The Book of Speculation and numerous short stories. Her debut bestseller follows two threads stitching together the story of 21st-century Long Island librarian Simon Watson with that of an 18th-century carnival troupe.

Just as that last sentence offers only the palest picture of everything contained in Swyler's rich, genre-defying book, so too "sit down, four hours, coffee" is a weak approximation of what Swyler's creative process entails.

Sometimes Swyler works on a laptop. Some days call for longhand in a notebook, writing with one of her preferred writing implements: a Le Pen in olive green or a Sharpie pen. "I love the felt tip pen and archival ink. They're wonderful," she told Spine. She also loves "little tiny stickies, the really small ones, and the Post-it flag. … Office supplies are writer's crack." Sometimes she composes on one of her vintage typewriters.

"It's different for each book and it's different for each character," Swyler said. "For some characters, if I'm working on a scene, for some reason that voice writes in cursive. If I switch to another character, that voice might be in print." For her current project, a novel centered on father-daughter duo in Florida in the 1980s, "there are a lot of scientific elements. When I'm working on the scientist [the father], I seem to only be able to write him on the laptop. Your body wants to find that character's speed."

Lately, Swyler's body has found its own speed: She's purchased a treadmill desk, which allows her to think and pace while remaining at work. She finds she's less likely to fall into the gaping time-sucking hole that is the Internet when on the treadmill. Writing longhand or on the typewriter also helps her avoid this modern-day trap, and keeps her plowing forward with the narrative instead of hyper-focusing on the minute details of each sentence.

Relying on her multiplicity of methods, Swyler pushes through her first drafts with relative speed, knowing she can return for thorough edits once she has the body of her story on paper. She likes to talk through plot points and character developments with writer friends — " I like to work it out out loud" — but doesn't allow anyone else into her new world until she's pinned down the primary elements where she'd like them.

"I don't like to let too many people see the baby too soon, because then I get opinions before I've formed my own. … It takes me a long time to figure out the heart of what the story actually is and what I'm trying to say. At the beginning, it's about everything. You don't know what you're writing about until you're at the end. Your subconscious knows the heart of the story much better than you do." Once she's satisfied she's found the meat of the thing, she solicits feedback from other writers and her agent.

Swyler's agent discovered her via her short story Transcontinental, published at Anderbo. With the agent's encouragement, Erika turned a draft into a polished story, and then turned her manuscript into art. At the heart of The Book of Speculation sits an old book, kept by a carnival master. To give her book the best shot of becoming a reality, to express the book's insides via a visual, tactile manuscript, Swyler spent months creating "old" books. She rasped, she stained, she guilded, she bound and at the end she had 16 beautiful books, 14 of which she sent off to agents.

Her gorgeous art and lovely words earned her a contract with St. Martin's, and a place at the design table. While she didn't choose the color, she was involved in most everything else. "I got to pick the colors for my endpapers. I got to say yes to having the ragged edge of the pages. There are several different typefaces, I got to choose them. I got to choose the second color for the printing. I got to see all these giant slugs of pantone colors. I really got a lot of input. It was a wonderful experience."

Swyler's book landed on the bestseller list, as well as several "best books" roundups at the end of last year. Swyler is back to the "sit down, four hours, coffee" routine on the next book, the aforementioned father-daughter tale. The project progresses as does all writing, in fits and starts.

"Some days I work for two hours and get 150 words. Other days, it's 2,000 words. The brain does not work quite as well as the body to get the extra mile," she said. "Some days you wake up and you're excited. And sometimes it hits you at the end of the day and you're excited to sit down. Other days, it's the same as getting up and going to the gym. You'll feel better after and you'll know you have moved along.

"For me, writing is a process of loving/hating something. It's the most enjoyable, detestable thing."

Find more Erika at erikaswyler.tumblr.com, at her food and humor blog, ieatbutter.tumblr.com, and on Twitter @ErikaSwyler.

Spine Authors Editor Susanna Baird grew up inhaling paperbacks in Central Massachusetts, and now lives and works in Salem. Her writing has appeared in a variety of publications, including Boston Magazine, BANG!, Failbetter, and Publishers Weekly. She's the founder of the Salem Longform Writers' Group, and serves on the Salem Literary Festival committee. When not wrangling words, she spends time with her family, mostly trying to pry the cat's head out of the dog's mouth, and helps lead The Clothing Connection, a small Salem-based nonprofit dedicated to getting clothes to kids who need them. Online, you can find her at susannabaird.com and on Twitter @SusannaBaird.