The Writer's Practice: Steve Rushin

During his 30-year career with Sports Illustrated, Steve Rushin has written in press boxes and hotel rooms, on airplanes and shuttle buses, and aboard a ship crossing the Drake Passage to Antarctica. But at home in Connecticut, where he composed most of his recent memoir Sting-Ray Afternoons, Rushin sits (or reclines) in a small home office surrounded by books, papers, folders, and not a few tchochkes:

• A hockey puck from the 1989 NHL All-Star Game in Edmondton

• Two mint-condition National League baseballs from the 1950s

• A poster commemorating the centennial of Manhattan pub urinals

• A poster advertising a 1932 Arsenal-Chelsea football match

• An NFL football signed by Hall-of-Famer Morten Andersen to Rushin's wife, ESPN analyst/Olympic medalist/former WNBA star Rebecca Lobo

• The catcher's mitt his grandfather Jim Boyle wore as a backup catcher for the '26 New York Giants

• A banana-yellow rotary telephone

• A miniature, working, fixed-gear bike with a chain and kickstand.

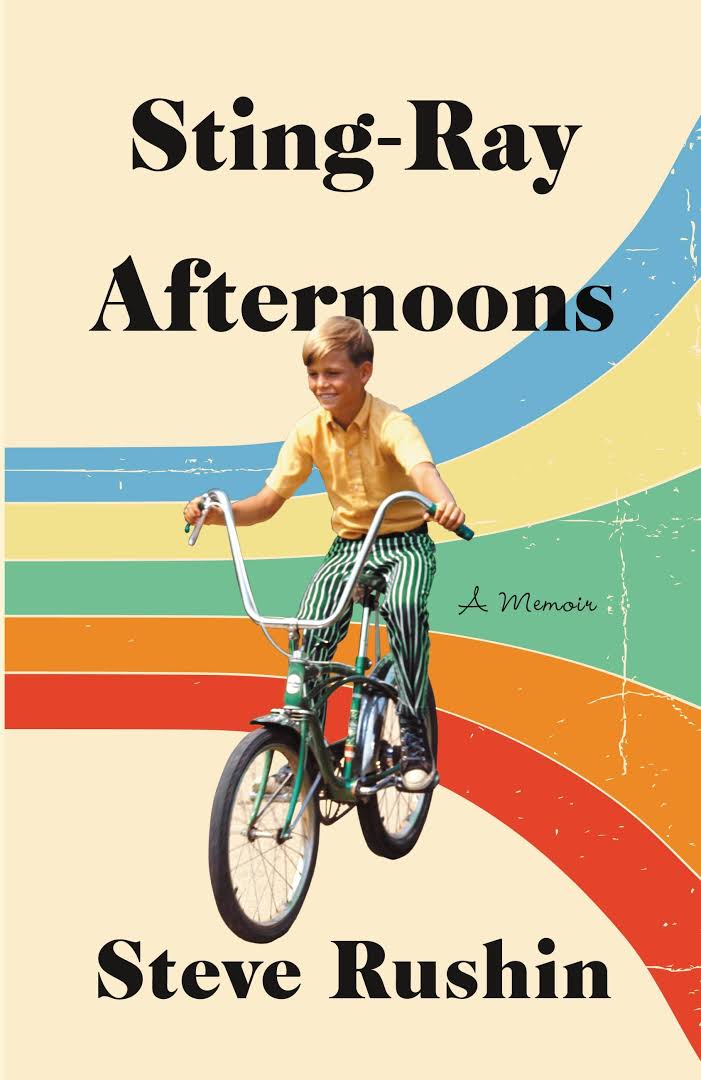

Rushin possesses a gift for using artifacts such as the Sting-Ray, found across America during the 1970s and on his book's cover today (thanks to designer Julianna Lee), to broaden a reader's sense of the worlds he's describing. Witness:

To hasten the arrival of adulthood, we ride Schwinn Sting-Ray bicycles modified to look and sound like motorcycles. It is a thing of beauty, a row of Sting-Rays parked in a driveway as if in the parking lot of a biker bar, our kickstands slowly sinking into the blacktop. Every driveway in South Brook is like that in the summer of 1974: kickstand quicksand.

Using words to recreate objects that characterize a specific universe, whether it be the Indiana of his boyhood or the bobble-headed, beer-cupped land of baseball (The 34-Ton Bat), is a skill Rushin developed on his day job at SI. Avoiding this same day job led him down a research rabbit hole that ended with Sting-Ray Afternoons.

"The memoir … began with me idly looking up the Chicago Tribune from the day I was born — September 22, 1966, in suburban Chicago," he told Spine. "My only reason for doing so was to procrastinate instead of writing a column." True to form, Rushin's attention settled on the pop-culture tidbits.

"I couldn't believe that a six-pack of Old Style [beer] was 79 cents and that the Yankees and White Sox drew fewer than 500 people to Yankee Stadium that night."

Looking at an ad for Star Trek, Rushin discovered the third episode aired an hour after his birth. "Did my Mom see it? It would certainly explain the Mr. Spock haircuts I had as a kid."

Rushin wanted more. "I looked at the next day's paper, and the day after that and the day after that. … And by then I … wanted to re-inhabit my own childhood specifically and the 1970s in general."

Spark lit, memoir research commenced. Mining his own memory banks and writing by hand, Rushin recorded as many recollections as he could retrieve. He grew increasingly fascinated not only by rediscovering the world he grew up in, but also by which memories hung tight.

"Why have I never forgotten riding to the beach in the back of our neighbor's green VW bug while Band on the Run played on the radio? If the book was going to be any good, it had to convey those moments, and also the boredom that was (and remains) a big part of being a kid."

Though Rushin himself would be the main cultural artifact at the heart of this book, he treated the process "as I would any other nonfiction assignment. I researched everything that interested me as a kid, returned to my old neighborhood, got the recollections of friends and family members."

He also gathered information on all the sensory pieces that would make the reader feel as if they, too, were inhabiting the 1970s. "It was important to get the smells and the sounds and the textures right. I try to do that in magazine journalism as well." Grabbing one object to include invariably led to the next object, and the next.

"I looked through old Sears catalogues and found so many of our home furnishings: my bedspread and pajamas and various Christmas presents that were under our artificial tree, which also came from Sears. There were set pieces that I wanted to include: a childhood sick day home from school, for instance, and the epic station wagon trips we took to Chicago and Cincinnati. Riding in the car led to other bits: about our wood-paneled Ford LTD Country Squire, or the litter that was so common on the highways, or the speed limit, or the ubiquity of hitchhikers, or the absence of seat belts."

Rushin pulled together several thousand words of narrative and shipped them off (via agent) to his Little, Brown editor John Parsley (now at Dutton). Parsley wanted more. Rushin wrote more, a chapter about his family's move from Chicago to Minnesota on the night of the '69 moon landing. "We stopped halfway in between in Wisconsin Dells, Wisconsin, and my parents watched Neil Armstrong walk on the moon before getting up the next day to start our new lives in Bloomington." The chapter rose up as a perfect and logical place at which to start the book.

Parsley played a key early role in helping Rushin chart a narrative course. Instead of writing a book about a personally significant set of 1970s objects, Parsley suggested he write a book about his childhood, peppered with objects but ultimately about his own personal journey. And it worked. Parsley and his colleagues at Little, Brown intimately related to Rushin's journey and its talismans, even if their own talismans came in different forms — Pokemon card collections, Atari consoles, little red wagons.

Though Parsley involved himself in the creative process on Sting-Ray Afternoons, Rushin mostly keeps his books close to the vest until he's finished. "It's not because I don't need or want the advice. On the contrary. It's more that I don't want to bother anybody with, 'Hey, would you mind reading my 90,000-word manuscript?' It's a lot to ask."

He does, however, chat with colleagues about the act of writing, about concepts and process. "My sportswriter friends are, generally speaking, the funniest people I know. They're a morbidly funny, grizzled group of armadillo-skinned cynics, many of them. And I love them. Talking with them generates ideas. And they're the few people who can understand specifically whatever it is I might be going through professionally."

One Sports Illustrated colleague, novelist and comedian Bill Scheft, provided Rushin his best bit of advice to date. Pondering a novel, Rushin asked Scheft if they could meet up and talk. "What's to talk about?" Scheft replied. "Either you're going to write it or you're not. Everything else is pretentious jibber-jabber."

Rushin's best piece of advice to other writers? Write.

"Books are not going to get written unless you pick away at them on a regular basis. You've got to swing the hammer and break the big rock into small rocks. It always amuses me when someone says, 'I bet that column wrote itself,' or 'That's the kind of book that writes itself.' No, no it isn't.

"Books do not write themselves. They are not self-cleaning ovens. 'That book writes itself' is the kind of thing said by someone who has never written a book, and never will."

Find more Steve Rushin at www.steverushin.com and on Twitter @SteveRushin.

Join us in celebrating the enormous talent that goes into making books. Consider a small donation to our Patreon fund. Your support helps us provide you with an in-depth look at some of the book publishing industry's most creative people.

www.patreon.com/spinemagazine

Spine Authors Editor Susanna Baird grew up inhaling paperbacks in Central Massachusetts, and now lives and works in Salem. Her writing has appeared in a variety of publications, including Boston Magazine, BANG!, Failbetter, and Publishers Weekly. She's the founder of the Salem Longform Writers' Group, and serves on the Salem Literary Festival committee. When not wrangling words, she spends time with her family, mostly trying to pry the cat's head out of the dog's mouth, and helps lead The Clothing Connection, a small Salem-based nonprofit dedicated to getting clothes to kids who need them. Online, you can find her at susannabaird.com and on Twitter @SusannaBaird.