The Avian Hourglass - An Interview with Author Lindsey Drager and Designer Steven Seighman

On August 13th 2024 Dzanc Books will publish Lindsey Drager’s fourth experimental novel, The Avian Hourglass. Here is a description of the book, taken from the publisher’s website:

At once an ode to birds, an elegy to space, and a journey into the most haunted and uncanny corners of the human mind, The Avian Hourglass showcases Lindsey Drager’s signature brilliance in a stunning, surrealist novel for fans of Jesse Ball, Helen Oyeyemi, Yoko Ogawa, and Shirley Jackson

The birds have disappeared. The stars are no longer visible. The Crisis is growing worse. In a town as isolated as a snowglobe, a woman who dreams of becoming a radio astronomer struggles to raise the triplets she gave birth to as a gestational surrogate, whose parents were killed in a car accident. Surrounded by characters who wear wings, memorize etymologies, and build gigantic bird nests, and bound to this town in which young adults must decide between two binary worldviews—either YES or NO—the woman is haunted by the old fable of the Girl in Glass Vessel, a cautionary tale about prying back the façade of one’s world.

When events begin to unfold that suggest a local legend about the town being the whole of the universe might be true, the woman finds her understanding of her own life–and her reality–slipping through her fingers.

A reflection on the intersecting crises of mental health, the climate emergency, political polarization, and the exponentially growing reliance on technology, The Avian Hourglass culminates in a figurative and literal twist that asks readers to reframe how they conceive of a series of concentric understandings of home: the globe, one’s country, one’s town, one’s family, and one’s own body.

I asked Lindsey to tell us more about the book and designer Steven Seighman to give us an insight into the creation of the cover.

Author Lindsey Drager:

What inspired the idea for your book?

I've found that for me, a project's origins come from the intersection of a set of questions or concepts. Often times as I am trying to grapple with one concern, I find myself turning to another and the space between them is where the answer tends to lie. For this book, I was thinking a lot about puppets and puppetry. The book started as a kind of 21st century feminist retelling of Pinocchio, but the more I wrote, the further I got from Carlo Collodi's original 1883 text. I was also writing a lot of plays -- or maybe one long play that I realized pretty early on could never be performed -- and so the question of playwriting and its relationship to puppetry started to get into my mind. I was asking myself: is a playwright like a puppeteer, governing the movement of the actors as though they were marionettes? Or was it unfair to think of actors as puppets, when each performance -- because of the actor's interpretations of the character on the page -- in turn "changes" the script? Does a puppet know they are controlled by other forces? What happens if they don't? What happens if they do? And then when the pandemic happened, I started watching the birds outside my bedroom window and imagining a world without them. So that intersection of elements -- a puppet who doesn't know she is a puppet, controlled by someone else; the idea of writing a play where the same script could lead to a series of different performances based on the script's interpretation; and the fear and sorrow of speculating on a world without birds -- all of these elements started moving together in my mind, getting tangled and braided until they seemed to be inextricably linked. That is when the book started to take shape.

What comes first for you — the plot or the characters — and why?

Strangely, I think for me the first element of the project is the form or the shape the story will take, the design of the structure itself. Once I've locked in the form, which is always connected to the ideas I want to explore or the questions I'm wanting to grapple with, then it is character. There are some writers who talk about there not being a divide between plot and character -- anything a character does, any act they perform is indeed plot and any plot is only moving forward, crafting cause-and-effect through a character's movement through time. But I tend to focus on the ideas or questions first, and then think about what kind of flesh vessel (other than my own!) might be also wrestling with these questions. So for me, a concept or idea comes first, which shapes the story's design, and then comes character. Plot -- the set of causally linked events that keep the reader flipping pages -- for me emerges out of the paper person's particular interiority on the page.

What themes do you explore in this book?

There are so many themes this book is dealing with in subtle ways, but the overt concerns orbit around questions of home and failure. The book concerns home in a variety of ways, from exploring non-traditional friendships and kinships and families to thinking through questions of belonging as it relates to the world, to one's nation, to one's town, to one's household. It is a book about what happens when the idea of home becomes unstable or precarious or contingent. It's also dealing with failure: personal failure when one doesn't live up to their life goals or experiences and existential failure in mid-life, but also global and national failures, whether species loss or political polarization. There are other themes bordering on these: the problems with binary thinking; the idea of coming to know oneself (which I see as distinct from coming-of-age); how to escape the narratives others craft for us and we craft for ourselves. What knowledge might be gained from seeing the world estranged. The power of not just speaking up or being heard or telling your story but also, maybe more so, listening: to others and yourself.

What is the significance of the chapters counting down?

The book is told in 180 parts that correspond to the 180 degrees of a half-circle. At the end of the novel, there is a kind of figurative (and literal) twist that asks readers to re-frame how they think of a series of ideas about home, from the level of the planet all the way down to one's own body. (There is a lot going on in the novel with The Uncanny.) So the countdown is really tightly wedded to the idea of the book operating itself like an hourglass -- everything counting down. If you think about an hourglass symbolically, the sand itself represents the present, the top of the hourglass is the future and the bottom is the past. The sand moves at a steady pace from the top to the bottom, but the sand itself is the present -- time moving forward or in this case down -- which is the only way the human mind can understand how time flows, even though physics says time does, in theory, run backward, too. This is also why the book is told in present tense. So the countdown is really a product of thinking about the hourglass as a narrative structure. But here is some proof that the reader constructs a novel as much as the writer does: an early reader told me they read the chapters of the book (which are very short and have elsewhere been described as fragments) as parts of a nest and the 180 sections craft half of that circular home, leaving it incomplete. I love that interpretation so much and I think it might even be a better reading of the 180 sections than my original hourglass idea. This is in part why storytelling is such a magical artform. Because texts are elastic and pliable enough to be read a number of different ways.

Did you have any say in the cover design?

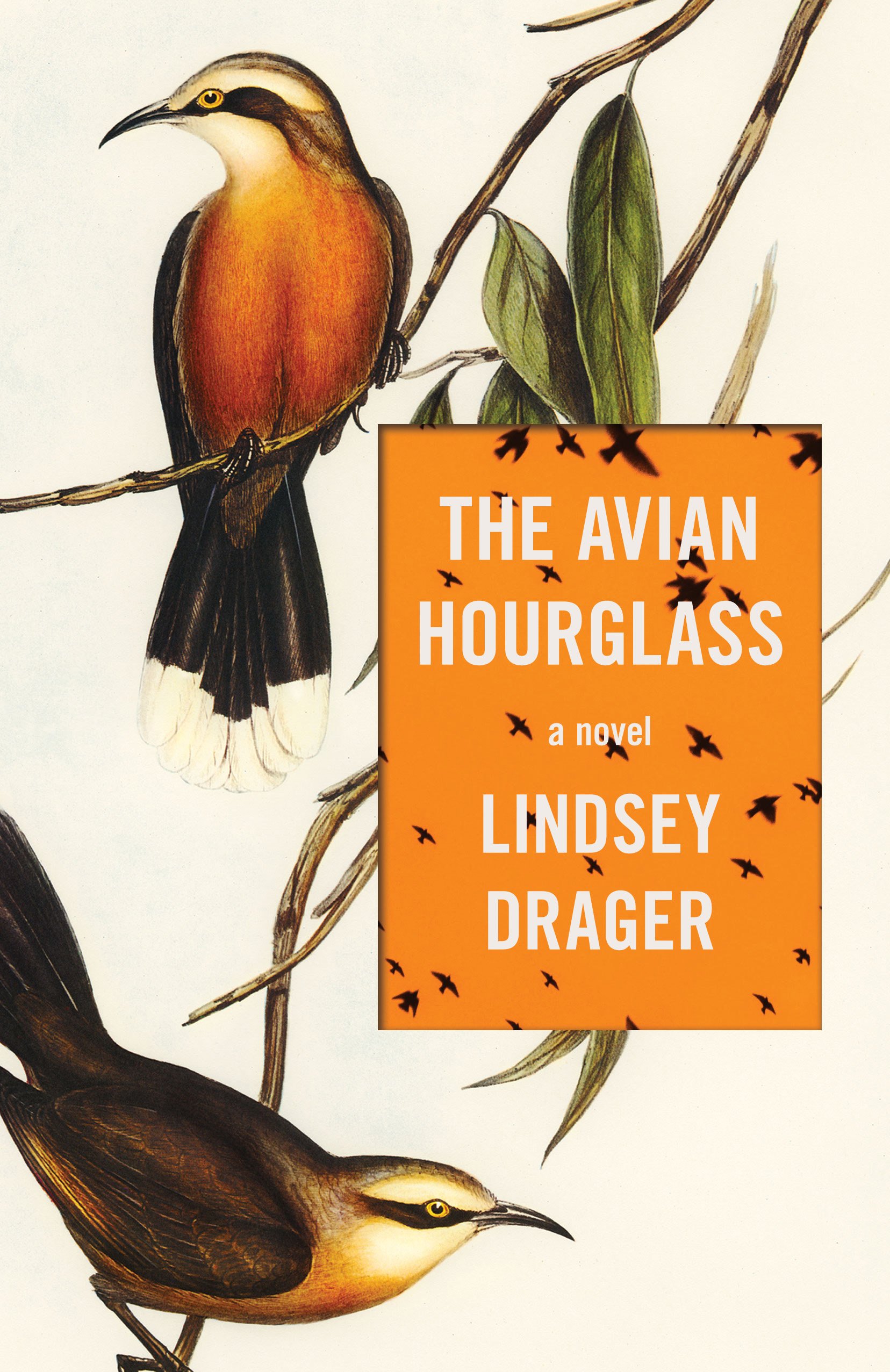

Yes, absolutely. Dzanc publisher Michelle Dotter looped me into the process of choosing the cover, for which I am very grateful. I know not all authors get this opportunity and I don't think it's a secret how important covers are (Spine Magazine itself has taught me this!). There were several extraordinary covers created for this book, some of which I still think about because they were so beautifully designed. Ultimately, though, I tried to convince Michelle the current cover was the best for pretty much one reason: the way the image on the front is framed. My other three novels -- all published by Dzanc -- have a very simplistic, very minimalist aesthetic.

What struck me about this cover was that the orange square in the bottom right with the sort of ghost-bird silhouettes reminded me so much of those other novels. But as it was presented here, it was as if the novel's cover (which would have matched the others Steven has designed for my other books) was embedded inside this avian frame. I don't know if Steven knew this about the novel, but this structure is essentially echoed in the novel itself -- there is a story-in-story framework that is revealed to the reader much earlier than it is revealed to the narrator-protagonist herself. (She was originally conceived of as a puppet who doesn't know she is a puppet, afterall.) So that idea of epiphany that a story is inside of a story was foundational to how the novel operated and -- to my mind -- it is also a core element of the cover we landed on. I love when covers offer not just beautiful imagery that set the tone for the reading experience, but also when they hint at something happening inside the book that the reader doesn't quite know about until the book is done. In that way, I think this cover in particular kind of winks or nudges you into a sense of both surprise and inevitability by the time you've read the novel, as if to say the revelation at the end was there from (before) the very first page.

Designer Steven Seighman:

Did you immediately know that you wanted to use illustrations or did you consider a photographic approach?

I did try a few photo-based designs before ending up with the illustration we used. But I think that while Lindsey's work is fantastical and fairytale-like, it also has a sort of scientific undercurrent to it and an illustration you might find in a textbook works well with it, especially for this book.

What other comps did you explore before arriving at the final design?

Birds and feathers, while a bit on the nose with the title, were always at the center of my sketches. Though, most of them were more abstract than what we landed on. The flock inside the title panel was carried over from one of the early iterations, so that gives you an idea of where we were in the beginning.

Tell me about the challenges of designing a cover for an experimental novel.

It's quite a fun exercise—finding symbols and a tone that fit an experimental story really opens up the realm of possibility. Sometimes that much freedom can get me into trouble though, so that can be a bit of a hurdle. In this case the editor at Dzanc had a few ideas early on that kept me in the right area for where we ended up, so my imagination didn't end up steering me off into some totally wrong direction.

Final cover

Editor, artworker and lifelong bibliophile.