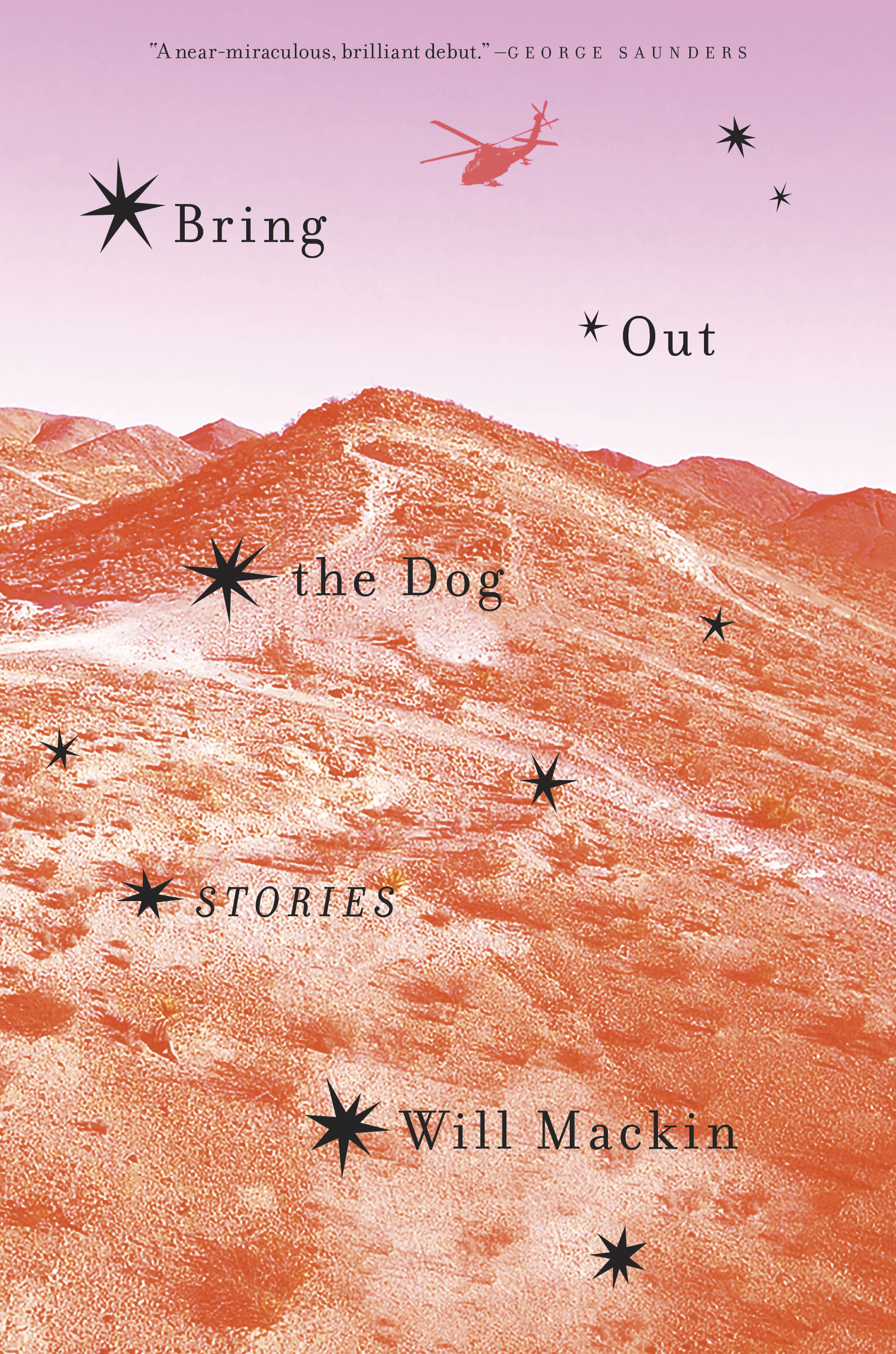

Will Mackin, Collecting his Experience as a Soldier in Bring Out the Dog

Photo courtesy of Elisabetta Mackin

"We were walking across the desert. It's like walking across the bottom of the ocean, rolling dunes of sand." Former Naval officer and writer Will Mackin, author of the new short story collection Bring Out the Dog, is telling Spine what it felt like, what it looked like to serve in Iraq. What it was like to serve in Iraq during that one minute, on that one day, that one moment that was so surreal, so ugly and so beautiful and so "fucking weird," he took out his grease pen and wrote notes across his arm. So he wouldn't forget. So he could carry the moment forward.

Back to it. Couple things you should know, to understand this one moment.

First, there's a lot of barbed wire in the Iraq desert, left over from the war with Iran, left over from wars with the United States. As trash collects in the ocean, forming massive garbage islands, so too does barbed wire coalesce in the Iraq desert.

So — "massive tangles of barbed wire."

Second, you should know about sparkle. Here's how Mackin explains it in the book. "We each had a device mounted to our rifles that generated sparkle — i.e., an infrared spotlight with a laser at its center. We used it to illuminate targets, and to see into dark places." Sparkle is a verb. "Lou sparkled a pile of trash." It's a noun, too. "Closing on the storm drain, Bobby hit it with sparkle."

So, sparkle.

Back to Mackin, moving across the Iraq desert with his unit. High above, a drone orbited, dropping a sparkle on anything they should be aware of.

"It dropped the sparkle on this giant tangle of barbed wire. It looked like the magic that turned Cinderella into a princess. The wind was blowing through it and it sounded like a UFO. We were in a hurry, and I didn't have time to stop and pull out a notebook." The barbed wire looked like a swan. Mackin wrote the detail on his arm and kept moving.

Mackin's time in Iraq, and his time training in the United States, was full of moments that came and went so quickly, he'd often feel like maybe they hadn't really happened. The sensory pieces — flashes of sparkle in the desert — and the action pieces — struggling to move an entire unit across a river, walking into unknown compounds and unfamiliar homes, with no clear picture of who and what waited inside — sometimes seemed a string of singular, disconnected experiences.

When Mackin retired in 2014, he pulled out all these pieces, this collection of sensory impressions and remembered actions, and dedicated himself, as a soldier and a writer, to figuring out the connections, and to capturing his experience for the people he'd served alongside. Grease pen thrown over in favor of a word processor, he started to write what he assumed would be a memoir.

"Initially I started writing this as nonfiction," he told Spine. "I felt an obligation to get it right. By that, I mean I wanted to represent everybody I served with. I wanted to capture the experience in a way that they would recognize, not just at face value, but emotionally. I didn't want to take liberties with their experiences."

Mackin held all the memories of these experiences inside him, but when he tried to get them out, the truth wouldn't come through in his writing. His truth, the connective truth, the unexplained lines that his mind had drawn between memories and people and sensations and even incidents from childhood — that truth dissipated when he tried to use facts to pin it down.

Take, for example, these pieces that Mackin's mind insisted belonged together: 20th century Russian writer Isaac Babel's short story Crossing the River Zbrucz. A guy Mackin served with in Afghanistan who, after falling into an irrigation ditch, cursed the mother of God. A football game from Mackin's high school years. A man Mackin served with, who drowned.

Mackin's mind said these elements belonged together, but nonfiction's insistence on reality meant they didn't. "I couldn't connect the things I felt were connected. Fiction allowed me to move around."

And so Mackin wrote fiction forward, towards a collection. Along the way he experienced a boost few early-stage writers receive: The New Yorker ran his first-ever piece of published fiction. "In a matter of days I had an agent and a book deal," he said. With help from his new editor, Andy Ward at Random House, Mackin labored for several more years. Ward shined a light — sparkled — on the strongest parts of Mackin's writing, helping him discover which directions worked best for his stories. The New Yorker ran several more pieces, as did other publications, culminating with the book's launch last month.

Though he's already arrived at a level of accomplishment few writers achieve, Mackin speaks humbly, thankfully of his success. "Whatever comes, it's gravy," he said. "I'm so grateful for whatever attention is put on this thing. It feels very good to have it done. I'm proud of it."

Find Will Mackin online at wmackin.com and on Twitter @mohammedsradio.

Spine Authors Editor Susanna Baird grew up inhaling paperbacks in Central Massachusetts, and now lives and works in Salem. Her writing has appeared in a variety of publications, including Boston Magazine, BANG!, Failbetter, and Publishers Weekly. She's the founder of the Salem Longform Writers' Group, and serves on the Salem Literary Festival committee. When not wrangling words, she spends time with her family, mostly trying to pry the cat's head out of the dog's mouth, and helps lead The Clothing Connection, a small Salem-based nonprofit dedicated to getting clothes to kids who need them. Online, you can find her at susannabaird.com and on Twitter @SusannaBaird.