Altering the Apparent: Translating Design

By Nuria Rodríguez

If like me you live, work and read in two or more languages and cultures, you may have noticed how the books that we love in one language sometimes suffer radical changes in another. And I am not referring to the words themselves—which for obvious reasons need to be varied—but to the whole book: its format, its layout and, more tangible, its cover.

In most cases the rights for the book to be translated have been acquired by a different publisher and it is up to them to have the title designed in any manner they deem appropriate; they may have their own house style or want to use a cover they feel is more culturally adequate for its new audience. Generally, the only rights acquired refer to usage rights for the translation and distribution of the text, not for its visual representation (with the exception of picture books).

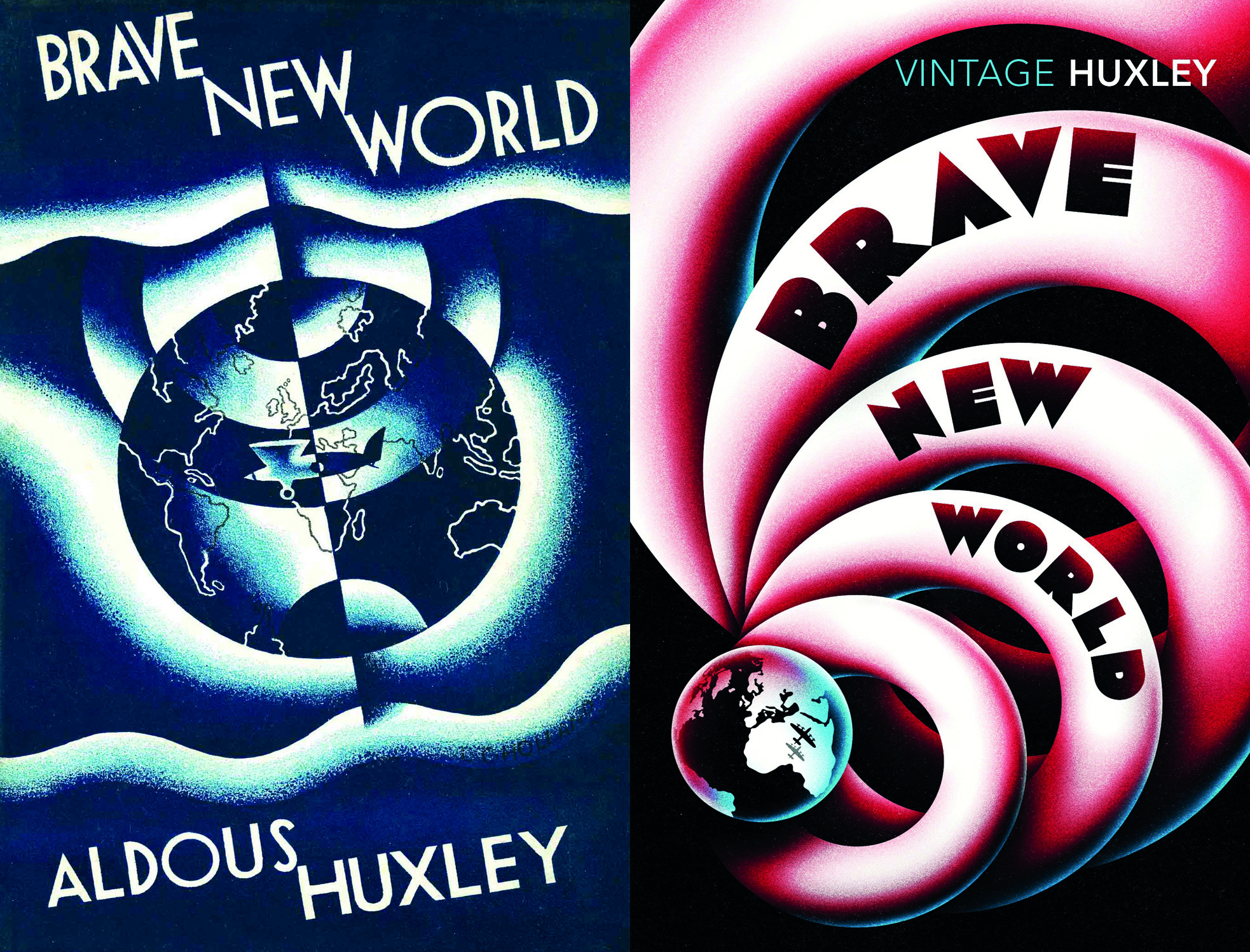

Even when not dealing with translation, it is not rare for a publisher to have two or more different covers for the same title within their list. The reasons may vary: from the relaunch of an old title trying to capture the imagination of a new readership, to the common film/TV adaptation syndrome. But it is always intriguing when a new title embarks on a trip across the seas to a country of shared language and still decides to change its clothes.

Let’s consider this matter from its purely advertising aspect. If we look at the cover as the visual representation of the brand—and the brand includes the author and a title in particular—then unquestionably the function of the cover would be to represent the values of the brand at that point in time. And it could be argued that these values remain unchanged through the book’s journey across various languages and territories. In fact, although the content is reshaped through a new language, the message endures. If the cover, then, is understood as a representation of these themes, it should by equivalence be equally unchangeable.

But there is also an artistic dimension worth discussing. Without getting into the dialectic around what constitutes art and whether the remit of graphic art is merely within marketing and advertising—artistic intention not being its main concern—there is undoubtedly artistic value in the design of the cover (and, I would add, in the form of the book). While the nature of the work of art demands an exclusive approach to the execution by the author and typically a unique point of origin for authorship—and by “authorship” we read an authority in the field—design, and especially design that responds to textual work, is collective and co-operative in character. The polysemic nature of text allows for a multiplicity of visual interpretations and the nature of design encourages numerous interventions.

When looking at textual content as art (stripped of its commodity condition), and open to multiple interpretations, the role of the designer becomes comparable to that of a translator. Their task is one of visually converting the meaning of the content and offering a personal version—try as they might, this is unavoidable—of the essence of the book. And this filtered visual representation, when done properly, captures the themes of the book and its core message. And since the message is not altered by its translation to various languages, or by the economic or cultural views of a new market, it could be considered to be universal and perhaps so should the cover.

There is one more element in the equation of interpreting text and its visual form, and that is the reader. If every different edition of a title constructs its meaning through the readership it is intended for in a particular era and place, then the final translation of meaning happens at the hands of the reader. And so, when the reader confronts a new work, or a new edition of a classic work, they are influenced by the object-book itself and all of its components, the first encounter being its cover.

This symbiosis of visuals and other forms of content is also present in other media forms. It would be hard to reimagine Peter Saville’s cover for Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures; the record-object is formed in our minds by its ultimate union of visuals, lyrics and sounds. Equally, the film The Third Man would have a quite a different feel without Anton Kara’s zither. Replacing the cover and removing the zither would not alter the storytelling of either piece, as the verbal/textual content would remain untouched, but the artwork-object would be radically transformed and would certainly lose some of its essence. Art can be interpreted in many different ways but we would not detach a piece of art from its context and re-dress it for a new audience, as we understand works of art as culturally sacred and, therefore, unchangeable.

And why should the cover art for books not deserve the same treatment? Forget for a moment about classic books from centuries past, when covers were merely considered for protection, when books were bound to match other volumes on the shelves, or even the interior decoration or the owner’s favourite gowns. They did not need to compete in today’s publishing market; they did not need to perform in a visually overloaded society. Concentrate instead on books published in the 20th century, works from the 1950s and the ‘60s that went through the same process as the books we design today. Think of book covers such as Shirley Tucker’s original design for The Bell Jar for Faber & Faber, Tony Palladino’s cover for Psycho for Simon & Schuster, or a contemporary cover such as Chip Kidd’s for Everything is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer (Houghton Mifflin). They all can, and have been, redesigned. Its content has been recovered —some more successfully than others—but that first unadulterated freshness that the original designer brought to the book by being the first reader, the first interpreter cannot be reproduced.

Not every artwork is held as fundamental to our cultural heritage. Equally not every book cover becomes an intrinsic part of the book. Still there are cases where the book cover achieves a perfect match for the content and becomes not just an expression of it but the expression of the book; contributing to elevating the book to a classic object status, even if this perfect match belongs to a particular expression in time and culture. If we believe that such a union can exist, then should the rights to reproduce the content also allow for the disembodiment from its shell? Maybe we should stop considering the cover as a disposable wrapper that needs to be altered to target various audiences, to speak various languages, and start regarding it as an intrinsic part of the work, an integral component of the book as object and the reading experience.

Welcome to our University Press Coverage — known as the Uni-Press Round-Up on the right side of the Pond — a monthly feature in which we highlight a selection of just-published university and academic cover designs, with commentary. Please enjoy this celebration of amazing work.

The selections are in alphabetical order by press. Where possible, credits are listed in the captions (often with links to the designers’ other work), and each cover includes a link to the university’s official page for that title.